This past October, I had the distinct pleasure of serving as a juror for the City of Evanston’s (IL) Cultural Heritage Awards program, sponsored by the City’s Preservation Commission, recognizing individuals and organizations who have made significant contributions to Evanston’s cultural legacies.

It was an honor to participate in Evanston’s preservation movement, which dates back many decades. Since the 1970s, a committed and enthusiastic group of preservationists and a supportive municipal government have led the charge to designate several historic districts and over 800 landmark properties—a significant preservation achievement for any community. One would be hard-pressed to find a city that could do that today. In comparison, right next door, Chicago, a city more than 47 times the population of Evanston, has only 450 designated city landmarks.

On a professional note, I had the opportunity to survey and inventory half the designated landmarks in 2015 as part of a Preservation Commission effort to document them fully – a task never before undertaken by the Commission in the many years of its landmarking program. It was an exciting assignment, taking photos and notes on Evanston’s vast range of historic architecture.

The award jury met to review several nominations for outstanding individual achievement, including three who have made outsized contributions to Evanston’s preservation scene: Julie Hacker and Stuart Cohen of their eponymous, Evanston-based architecture firm, and Jack Weiss of Jack Weiss Associates and founder of Design Evanston. Design Evanston is a design advocacy and education organization. All three have had an immeasurable impact on Evanston’s preservation efforts and its urban environment through their design work and involvement in Evanston’s preservation program.

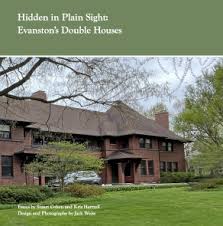

As part of our deliberations, the Preservation Commission invited nominees to meet with the jury and present their resumes and records of accomplishment. It was the first time I met Jack, Julie, and Stuart in person—three legendary preservation heroes in Evanston. And speaking of books, I learned from our conversations with them that they recently collaborated on a new publication—In Plain Sight: Evanston’s Double Houses—about Evanston’s storied “double houses,” published under the auspices of Design Evanston and written with Kris Hartzell, a longtime architectural historian with the Evanston History Center.

Historic double houses are rare. They are akin to duplexes in that they often appear as single-family homes with two entrances designed and placed rather inconspicuously to visually deceive one into thinking they are single-family houses. Duplexes today, generally, do not try to hide their two unit configuration. This may be hair-splitting on the terminology between double houses and duplexes but many of Evanston’s double houses will certainly fool you—they look like single-family dwellings.

Double houses are not common in most of the Chicago area—well, most communities, for that matter. That’s why cities today are trying to build them—they are missing in housing mix. But I have come across historic duplexes here and there in my various travels, in Texas and Arkansas—fine examples of well-styled dwellings that blend in exceptionally well in their neighborhood context. They make latter-day duplexes look bulky and clumsy, especially with their front-facing “snout” garages rather than front porches, as is common in most historic duplexes.

But duplexes are back in vogue as part of the “missing middle” campaign to add more housing in our cities. Evanston has the original, however, with several protected as individual landmarks, with others located within one of the six local historic districts. Evanston already has the prototype that so many other communities are striving to add and designed in styles and forms that seamlessly blend with the single-family dwellings that make up Evanston’s historic neighborhoods.

Hidden in Plain Sight catalogs all the known double houses in Evanston in short history essays that describe each house’s first owners and the investors and developers who built them. Accompanying each essay is a photograph of the subject house taken by Jack Weiss’s experienced hand. Jack, in addition to being Director Emeritus of Design Evanston, is also an accomplished graphic designer, writer, and photographer. Cohen and Hartzell take turns on the individual house essays. The book also provides an introductory narrative on the history of the double house in Evanston and its characteristic features, from its typical floor and room arrangements to its exterior elements that make it appear as a single-family home rather than the snout duplexes of today’s vintage. The vast majority of the double houses in Evanston were built from the 1890s onward as the city grew and gained distinction as a pleasant place to live away from Chicago’s hustle and bustle.

Both Hartzell’s and Cohen’s essays, complemented by Weiss’s perfect and exacting photography, offer a compelling glimpse into house building unique to Evanston, but never really caught on anywhere else. The reason for this is somewhat mysterious—why Evanston? Both Cohen and Hartzell never quite answer that question entirely, but it was likely due to circumstances: as Chicago recovered from the Great Fire of 1871, Evanston, located on Lake Michigan, became a desirable place to build. Land became more expensive, and double homes, rather than apartments, became easier and more suitable to build within the city’s developing single-family neighborhoods. It just made sense here.

Evanston’s double houses, on the whole, are wonderfully conceived design solutions that accommodate extra density without compromising neighborhood appearances. They range in architectural style from Queen Anne to Dutch Colonial, and from Shingle to Prairie and Georgian Revival. The book also features a few more recently designed double houses, demonstrating how today’s architects use simple forms and a refined material palette that mark them as new but still fit exceptionally well within their context.

I’m sure most visitors to these neighborhoods would recognize them as single-family homes. In some cases, the architects and builders of these houses devised ingenious ways to place the entry porches to obscure or hide the front doorways, belying the fact that these are two housing units when the facade facing the street presents itself as one. Can builders today, in the missing-middle housing frenzy, achieve the same result? We shall see.

This book is an enjoyable and fascinating read. I only wish there were a map showing where the houses are, in case readers, including myself, wanted to tour the homes on their own someday.

Many thanks to Design Evanston, and to Hartzell, Cohen, and Weiss for illuminating a largely unknown and underappreciated part of Evanston’s architectural legacy. As I was reading the book, I discovered a double house that I know rather faintly from that survey from ten years ago. It was a house I surveyed. I think I classified it as a single-family home rather than a double house, as it is. It tricked me. Only an Evanston double house can do that.

All photos by Nicholas P. Kalogeresis, AICP

Leave a comment