The discussion on adaptive use in the mainstream media has been gaining ground in recent years. There is not a week that goes by when there is a report on a signature building somewhere being resurrected from the doldrums of vacancy and neglect into something dramatically new and regenerative. A case in point – the rehabilitation and reopening of the Michigan Central Building in Detroit this past week, once a long-forgotten icon of that city’s past now reborn as a new cultural and technology hub (read Michigan Central is Open). It is another tangible symbol of Detroit’s comeback. This story and many others are now routinely making it into outlets like Bloomberg CityLab, Forbes, and the New York Times. ArchDaily, the digital newspaper on architecture, regularly posts news on noteworthy adaptive use projects from around the world. Local newspapers are also providing more coverage as cities deal with underutilized and vacant office buildings on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, this is good news as preservation gets a public boost to its utility – old buildings are not a hindrance to progress but an avenue to dealing with pressing economic realities. It also helps save the planet – it is recycling to its utmost degree. It is also a nice tonic to the many recent opposing views written by journalists claiming that preservation is bad for cities (start with this: When Historic Preservation Hurts Cities).

In addition to the everyday coverage in newspapers and websites, adaptive use is now the subject of a new book: Transform: Promising Places, Second Chances, and the Architecture of Transformational Change, written by architect and Dean of the Yale School of Architecture Deborah Berke, and architecture critic and Adjunct Professor of Architecture at Columbia University, Thomas De Monchaux. Berke is also a founder and practicing principal with TenBerke, a New York City-based architecture firm with a specialized practice in adaptive use. The book focuses on the various adaptive use projects the firm has been involved in over the years, including ones located in New Haven and New York City, but also as far as Louisville and Oklahoma City. This book nicely fills in the gap in publications regarding adaptive use and preservation architecture in general. Monographs on architecture today almost always exclusively focus on the works of a few starchitects while literature on adaptive use seems to be relegated to technical pamphlets for professional preservationists. So, Berke’s and Monchaux’s book comes at an interesting time and fills a void in recognizing the work of preservation architects. And why not – preservation architects deserve to be celebrated just as much as the starchitects. Who might be doing more for the planet right now?

The book’s title implies its main theme – the transformational power adaptive use has in resurrecting old buildings from neglect and abandonment to producing new spaces that offer possibilities for revitalizing the economic, social, and environmental character of communities. To Berke, transforming buildings involves a methodical process of understanding a building’s past – what merits keeping that acknowledges and expresses the past but also contemplates the needs of current and future generations who will use the building. It is essentially a three-way dialogue between past, present, and future on making an adaptive use project work.

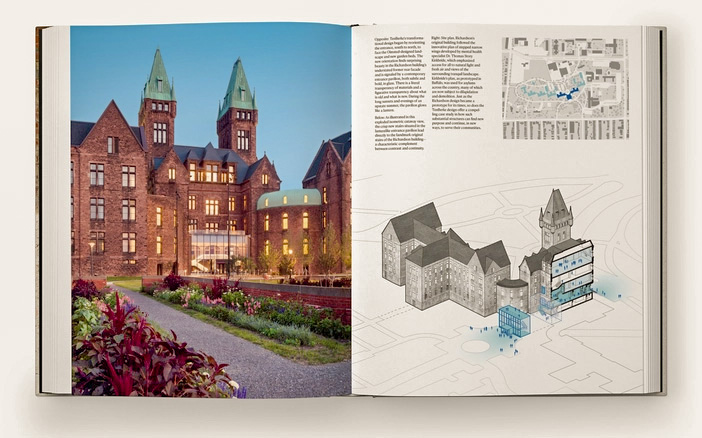

The book’s twelve case studies from a former Henry Hobson Richardson-designed mental healthcare asylum in Buffalo, New York to a photography studio in a once-functioning auto garage in New York City demonstrate Berke’s thinking. All of them are buildings transformed with spaces that offer flexibility and continuity from the past into the future. However, Berke is no doctrinaire preservationist. For her, one must explore a spectrum of interventions that adapt buildings to achieve their latent promise of transformation – a “creative use” to be more exact. Therefore, if you were expecting a publication on by-the-book U.S. Secretary of the Interior Standards-approved case studies this is not it. Expect some descriptions of truly creative and provocative projects. Nonetheless, each case study suggests approaches to adaptive use, from minimal interventions that complement the existing context to elaborate and dramatic schemes that add more functionality and purpose.

In addition to the case study on the former Buffalo Asylum for the Insane – one of the more monumental Richardson designs you will ever find set within a park-like campus designed by Frederick Law Olmsted – the book features projects on buildings designed by other noteworthy architects. For instance, the path taken to adapt the Louis Kahn-designed Jewish Community Center built in 1954 in Kahn’s trademark version of the International Style and reimagined as Yale University’s new School of Art, demonstrates how careful “redeployment” of interior spaces can make for intriguing new studio and gallery spaces that also preserve and respect the visual clues of the building’s past use. The Community Center’s former swimming pool. for example – now converted to a critiquing lab studio – retains its swimming lane markings. The gymnasium and its handball courts, largely unchanged in form, also now serve as galleries. This restrained approach provides new meanings and purpose for the building – old spaces have new futures for creative endeavors. The Yale School of Art and the Buffalo Asylum for the Insane – now in use as the Richardson Hotel – are both adaptive efforts we come to know with materials and architecture intact with minimal intrusions to their original form and appearance.

But the rest, more fascinating adaptive use projects are those that have dramatic change – ones that take us into new adaptive use directions. Take, for instance, the Rockefeller Arts Center on the Campus of SUNY-Fredonia and the Lewis International Law Center at the Harvard Law School. Both projects take rather unassuming Brutalist and late Mid-Century academic buildings – with I.M. Pei and Partners the architect of record for the SUNY campus buildings – and renews them with dramatic additions that at first appear quite imposing and monolithic but seem right for the use needs and design approach taken. The additions in both cases sport new upper story volumes of titanium skinned fins that front glass curtain walls, complimenting and reinforcing each building’s Modernist and Brutalist design vocabulary. The additions offer much-needed space for classrooms, studies, and performance spaces. Preservationists may question whether these are pure adaptive use projects given the scale and size of the additions – are they entirely new buildings? The point made by Berke and Monchaux is the prospect of transformational change and giving second chances to old buildings when alternatives may not be possible and purposeful.

Three other case studies are worth mentioning. Two adaptive use projects, one in Louisville, Kentucky, and the other in Oklahoma City are interesting case examples of how precise incisions and small-scale additions in existing buildings, rather than substantial volume accretions, can make historic buildings come alive again. The Oklahoma City project converts an old Ford Motor Company building, designed by a different Kahn – Albert Kahn – into a hotel. It is my favorite case study in the book – the outward utilitarian façade with its brick-accented ornamentation presents a simple but majestic statement in its newly rehabilitated state. The interior concrete columns and its blank white walls are all that is left of its factory interior. The new interior light wells carved into the building, faced with glass block brighten the hotel rooms to a point where the rooms and floors seem almost transparent.

One other project is worth mentioning, an unfulfilled one that sought to adapt a former women’s prison into a center for women’s empowerment that starts the book’s case study discussion. The Women’s Building project, which sought to reuse a former YMCA that served sailors disembarking from now-defunct ports in Manhattan, and later used as a woman’s correctional center, held promise as a building for the spiritual renewal of those once incarcerated inside. After an extensive community engagement process, the building’s future use scheme including the preservation of several cell spaces as a means to interpret the building’s past use for women confinement and detention. Unfortunately, the Covid pandemic prevented the project from going forward.

There’s much to enjoy about this book. The case studies feature both traditional adaptive use projects we come to know where the approach is rehabilitation-restoration to the more dramatic tactic of adding new additions, floors, volumes, and cuts and excisions into the building fabric that aim to make the existing more useful for the future. It is well illustrated with photos and blow-up isometric drawings that provide perspectives on the building changes that made way for the old to have new life. Its narrative is written mostly by Monchaux who describes the thinking behind the adaptive work, often as conversations between Berke and her project principals-in-charge and associates. While Monchaux’s writing can be loquacious at times, it never stops being stimulating – the decisions on how to adapt buildings are just as consequential as what goes into the designing of new ones.

Besides the case studies, there are short essays on the environmental benefits of adaptive use and one titled, “Time is that Collaborator,” a summary discussion between Berke and the executive director of NXTHVN, Titus Kepler. NXTHVN is another of the book’s case studies on how two low-scale historic industrial buildings were joined together by an addition to create a community arts center in a New Haven neighborhood. The essay captures the essence of what adaptive use should be focused on: while we try to understand what stays or goes in adaptive use – that conversation with time is ultimately about saving and transforming spaces for people. In a time when adaptive use will be ever so more important for addressing climate change and the economic and social well-being of our communities, we need architects like Deborah Berke. And more books like Transform to advance the conversation.

Image of the Michigan Central Station at the top of post courtesy of the Wayne Andrews Archive (Esto) and original data provided by Estate of Wayne Andrews and the Society of Architectural Historians.

Leave a comment